One of my chemical heroes is William Perkin, who in 1856 famously (and accidentally) made the dye mauveine as an 18 year old whilst a student of August von Hofmann, the founder of the Royal College of Chemistry (at what is now Imperial College London). Perkin went on to found the British synthetic dyestuffs and perfumeries industries. The photo below shows Charles Rees, who was for many years the Hofmann professor of organic chemistry at the very same institute as Perkin and Hofmann himself, wearing his mauveine tie. A colleague, who is about to give a talk on mauveine, asked if I knew why it was, well so very mauve. It is a tad bright for today’s tastes!

Charles Rees, wearing a bow tie dyed with (Perkin original) mauveine and holding a journal named after Perkin.

The first thing to note about mauveine is that it is not a single compound; actual samples can contain up to 13 different forms! These all vary in the number of methyl groups present which range from none up to four, in various positions. These compounds all have absorption maxima λmax in the range 540-550nm, the colour of purple. The structure of one of these, known as mauveine A, is shown below.

Mauveine A. Click to load 3D

This has several noteworthy aspects.

- The visible (right hand side) part of the spectrum is very monochromatic, with λmax ~440nm. In other words, mauveine has a pure and intense colour.

- This λmax is hardly affected by the presence of the counterion.

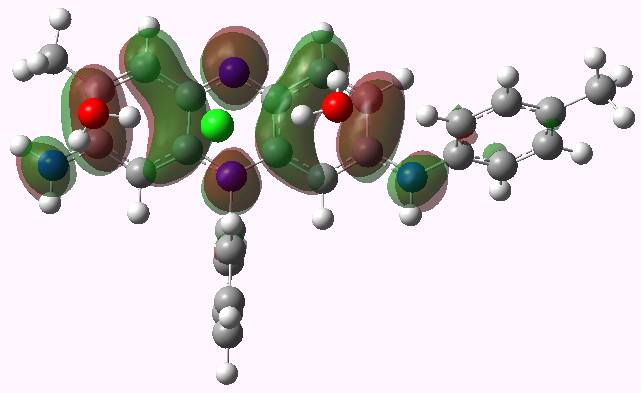

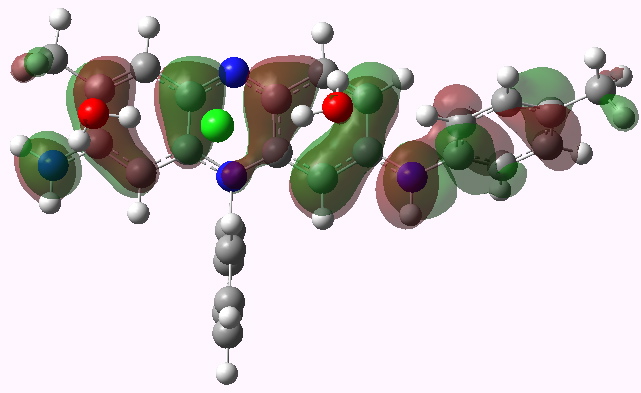

- The electronic transition responsible for this band is a simple HOMO (highest-occupied-molecular-orbital) to LUMO (lowest-unoccupied-molecular-orbital) excitation of an electron.

- These orbitals are shown below.

LUMO HOMO

Mauveine A. LUMO. Click for 3D

Mauveine A. HOMO. Click for 3D

- Note how the excitation involves the central region of the molecule, and one of the pendant aryl groups, but not the other. One might presume that tuning the colour would only work if changes are made to the first of these aryl groups.

- There is a real mystery about the calculated value of λmax, which differs from the observed value by about 100nm (the wrong colour, making mauveine orange rather than purple). Normally, this sort of time dependent density functional theory has errors no greater than 15-20nm. The calculated value of λmax is not sensitive to the basis set, or the presence or not of the counter ion and solvent. Clearly, a discrepancy of this magnitude must have some other explanation. Watch this space!

So this post ends with a bit of a mystery. The fanciest most modern computational theory gets the colour of mauveine wrong by ~100nm. Why?

Tags: August von Hofmann, Charles Rees, chemical heroes, chiroptical, colour, founder, Historical, Hofmann, HOMO, Imperial College, Imperial College London, LUMO, Mauveine, Perkin, professor of organic chemistry, purple, Rees, Royal College of Chemistry, William Perkin